By Ahmad Novindri Aji Sukma, Regulatory compliance lawyer based in London and PhD researcher at the University of Cambridge, and Iqbal Natio, legal researcher specializing in Environmental and Economic Law.

During the last weeks of 2025, Indonesia faced one of the deadliest environmental disasters in its recent history. Torrential rains swept across Aceh, North Sumatra, and West Sumatra, submerging whole districts, collapsing bridges, and sweeping away houses in waves of mud, logs and debris. According to the National Disaster Management Agency (BNPB) data at the end of 2025, the toll is staggering: over 1,150 confirmed deaths, hundreds missing, and nearly 400,000 still displaced. While these figures represent a human tragedy, through the lens of climate governance, they reveal far more complex and troubling stories.

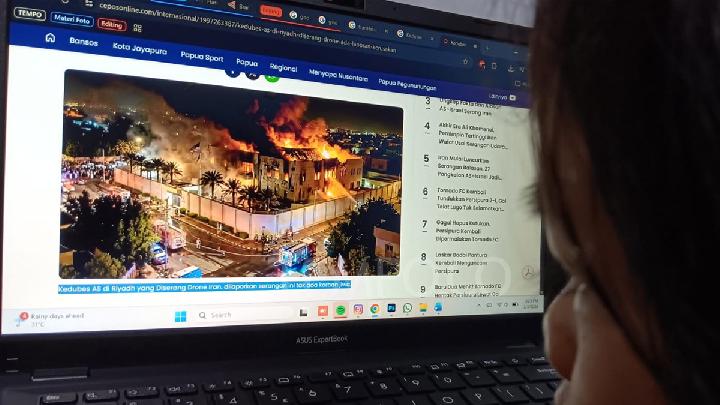

Satellite images and drone footage circulating on social media show massive piles of logs stacked like matchsticks floating along river channels and scattered across floodplains. In Pantai Air Tawar, Padang (West Sumatra), residents awake to coastlines littered with hardwood logs. In Aceh Tamiang, entire neighborhoods lie buried under mud and uprooted trees.

Such scenes show much more than floods. They point to a deeper chain of environmental abuse. Timber in such quantities does not appear overnight, it is the legacy of upstream deforestation and land clearing. What should have been a forest canopy, capable of absorbing rainfall and anchoring the soil, was stripped bare, replaced by exposed soil prone to catastrophic runoff and landslides.

The disaster cannot be read as a “natural event” alone. It reveals structural weaknesses in Indonesia’s environmental governance, weaknesses exacerbated by recent legal reforms.

The 2023 Omnibus Law on Job Creation significantly streamlined investment approvals, but it did so by diluting environmental safeguards. Critics have long warned that weakening Environmental Impact Assessments (AMDAL) and curbing public participation would invite catastrophe. The floods in Sumatra are the living testimony of those warnings. A regulatory environment that once subjected logging, plantation, and mining to robust oversight has been hollowed out. When the institutions designed to manage risk are thinned, climate hazards multiply the moment extreme weather hits.

What makes this disaster significant is its timing. Only weeks before, at COP30, Indonesia reaffirmed its commitment to combating deforestation, strengthening nature-based climate solutions, and building climate resilience. Yet, within days, the country witnessed devastation that appears fundamentally inconsistent with those promises. This is Indonesia’s first real test since COP30, not on the global stage abroad, but at home. The contrast between diplomatic pledges and domestic realities raises a critical question, ‘What does it mean for a state to commit to climate action if its regulatory frameworks enable the very practices that fuel climate disasters?’

Furthermore, the legal landscape has shifted. In July 2025, the International Court of Justice (ICJ) issued a landmark Advisory Opinion clarifying states’ binding legal obligations under international law to prevent, mitigate and remedy climate harm. The Court emphasized a duty of due diligence, requiring states to regulate private actors whose activities contribute to environmental degradation and climate risk. Failure to control those actors does not absolve the state of responsibility, it deepens it.

Under this emerging global standard, the stripped hillsides and choked rivers of Sumatra are more than a domestic tragedy; they may constitute a breach of Indonesia’s international obligations.

The aftermath of these floods – the timber debris, chaotic hydrology, flooded settlements - is not just proof of environmental mismanagement. It may soon be seen as evidence in an era where climate negligence carries legal consequences.

The Sumatra catastrophe is not simply a disaster to recover from. We have to see this as a warning that deregulation and weak enforcement in the name of economic growth can backfire catastrophically when extreme weather events become more frequent and destructive under climate change.

More importantly, in a post-ICJ world, failing to prevent foreseeable environmental harm can be considered as a violation of international law obligations.

If Indonesia intends to honor its domestic and international climate pledges, it must take five decisive actions. First, it must reinstate strong environmental safeguards by restoring the integrity and enforceability of AMDAL, ensuring the review process is transparent and allows meaningful public participation.

Second, it must strengthen oversight by granting regulatory bodies the resources, authority and independence necessary to monitor and sanction violations. Third, it must restore degraded ecosystems through large-scale reforestation, watershed rehabilitation, and sustainable land-use planning.

Fourth, it must hold perpetrators accountable by imposing more robust sanctions, restoration orders and strict liability on logging firms, plantation companies and financiers that operate in defiance of regulations. Fifth, it must align development with climate resilience by incorporating scientific-based risk assessment into all development planning, and treating forests as critical ecological infrastructure rather than exploitable assets

The Sumatra floods are a brutal reminder that climate change no longer exists in the abstract, its consequences are measured in lives lost, ecosystems destroyed, and human suffering. They demonstrate that deregulation pursued in the name of investment can come at the cost of ecological resilience and human safety.

In the wake of the ICJ’s advisory opinion, regulatory failure can no longer be chalked up to “domestic administrative matters”. It may constitute international climate liability.

After COP30 and the ICJ’s watershed ruling, the world will judge Indonesia not by the rhetoric it brings to the global stage, but by whether it protects its forests and its people at home.

*) DISCLAIMER

Articles published in the “Your Views & Stories” section of en.tempo.co website are personal opinions written by third parties, and cannot be related or attributed to en.tempo.co’s official stance.

:strip_icc():format(jpeg)/kly-media-production/medias/5357081/original/011599400_1758518426-expressive-young-girl-posing.jpg)